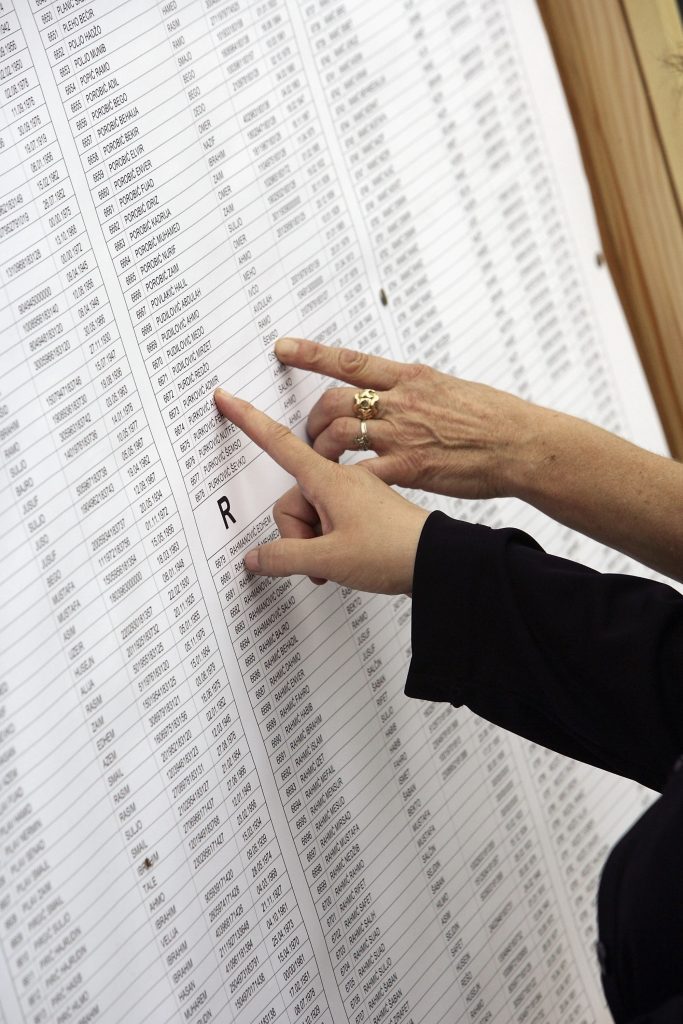

In this 2005 file photo, relatives of some Srebrenica massacre victims check names on sheets at the Srebrenica Memorial on July 9, 2005 in Srebrenica, Bosnia, Herzegovina. The Connecticut General Assembly is considering declaring July 11 as Bosnian Genocide Remembrance Day.

Now these CT residents seek to commemorate the 1990s Bosnian genocide.

Alma Huric of Hartford remembers July 11, 1995.

“The Serb forces gathered up all the men and boys within their reach, tortured them, killed them, then buried them in mass graves around the Srebrenica region. My father and his two brothers were among those who were killed.”

Huric and two dozen more Bosnian-Americans offered testimony this week to the state legislature’s Joint Committee on Government Administration and Elections.

The public hearing pertained to SB1158, which seeks to assign days, weeks and months to various commemorations: Trinity College Day, Ann Petry Day, Peace Corps Month, Free Enterprise Day, diseases needing awareness, etc.

But the testimonials were dominated by one heartbreaking paragraph in the bill. Survivors of the 1990s Balkans atrocities, now living in Connecticut, rallied to support July 11 being declared Bosnian Genocide Remembrance Day.

The Srebrenica massacre, which began July 11, 1995 and killed 8,372 men and boys, came near the end of years of violence committed by Serbs against Muslim communities in Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Testimonials told horrifying stories of lives destroyed. Murat Efendic of Rocky Hill recalls July 11, too. He lost two brothers in Srebrenica.

“The women and children were put on buses, while the men and young boys were killed execution-style. It was an attempt of extinguishing Bosnian males in an effort to take out the Bosnian race and culture,” Efendic testified.

Zahid Begic of New Britain escaped Srebrenica.

“We did not know what was happening to the men and young boys who did not make it out of Srebrenica. We did not know they were being killed execution-style. We ourselves, were being ambushed left and right, many men being killed through the forests,” Begic said.

Earlier atrocities

Many testimonies focused not on Srebrenica, but on the killings of Bosnians in the years before that massacre. Halid Dervisevic of Hartford gave one of those accounts:

“A few months into the war, my mother returned home to secretly collect crops from the land to feed her children. In the process of collecting the crops from our land, my mother was shot by a sniper from a neighboring village of Bosnian Serbs. She became one of the first civilian victims of the war. Her last words were ‘O moja djeca.’ She uttered ‘O my children’ as her last words.”

Munisa Suljic-Aly of Wethersfield said her mother acted as a human shield to protect her.

“My childhood unfortunately consisted of fleeing my home, living in the fear, fighting for my life, starvation and hunger, running from the bullets, bombs, tanks, hiding in the woods, sleepless nights, and endless walk to ‘safe zone’,” Suljic-Aly remembered.

‘Never again’

The bill was sponsored by Sen. Saud Anwar (D-3rd District). Anwar said one of his interns, Bekir Hodzic of Hartford, the son of Bosnian immigrants, inspired him to add the July 11 proposal to the bill.

“Genocides have happened through human history. The Holocaust is the worst we can recall. Every time we think about it, there is an emotion generated in our hearts: Never again will we allow this to happen.’ Unfortunately this happened despite that promise,” Anwar said.

“It’s important for us to pause occasionally to reflect on what has happened and check on status of the planet, to see if similar hatred based on ethnicity or race or belief or religion … is being used to attack communities.”

Hodzic participated in the public hearing. He stressed the importance of reporting factual history.

“Today, genocide denial runs rampant in Bosnia. It’s even present in America, with laypeople and academics alike trying to revise history to paint Bosniaks as liars and aggressors,” Hodzic said.

“In a world where crimes against humanity seemingly proliferate … saying nothing forms a dangerous precedent. Let us set a better one and make ‘never forget’ mean something.”

Battling denial

Dr. David Pettigrew, professor of philosophy at Southern Connecticut State University in New Haven, attended the hearing. Pettigrew created a course “Holocaust and Genocide Studies” and works with the Connecticut Holocaust and Genocide Education Advisory Committee.

Pettigrew, like Hodzic, mentioned the denial in Bosnia. The most recent high-profile denial was by Milorad Dodik, president of Republika Srpska (part of Bosnia and Herzegovina), who said on Feb. 21 “Genocide did not happen there. We all know that here in Republika Srpska.”

Pettigrew said commemorating genocide helps fight denial.

“In Bosnia there are atrocity sites, concentration camps and execution sites where authorities will not allow memorials or even a plaque,” he said. “Elie Weisel once said, ‘To forget the dead would be akin to killing them a second time’.”

He added that commemoration may prevent future genocides.

“In Greg Stanton’s ‘The Ten Stages of Genocide,’ denial is the 10th stage and the surest indicator there could be a repeat of the atrocities. Telling the truth is part of genocide prevention,” he said.

Zehrudin Mujcinovic of Southington had a simpler explanation for supporting the commemoration: It would help him talk to his children.

“[It] will make it easier for me to explain to my kids why their parents are here and why they never met some of their grandparents and other members of their family,” he said.

(https://www.courant.com/)